https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjpc/zwad403

Authors: Zihao Huang, Rihua Huang, Xinghao Xu, Ziyan Fan, Zhenyu Xiong, Qi Liang, Yue Guo, Xinxue Liao, and Xiaodong Zhuang

What We Already Know:

Based on institutional guidelines (American College of Cardiology, European Society of Cardiology, WHO), the general consensus is for adults aged 18-65 years to exercise at least 150 minutes each week at a “moderate intensity” or at 75 minutes/week at a “vigorous intensity.” However, as you’ve probably noticed, this statement lacks specificity — for example, what does that need to look like, what exactly does moderate intensity mean, what if one misses a week or two of exercising here or there? It’s obvious that people live busy lives, and knowing what the minimum dose required to get most — or some — benefit from exercise would be huge. Not to mention, the vast majority of cardiovascular events (heart attacks, strokes, etc.) happen later in life, and while most of us can intuit that your probably need to be exercising during your youth to hopefully prevent issues down the line, there really haven’t been too many studies to directly study this.1

What Was Done:

Huang and his colleagues used data from the CARDIA (Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults – NCT00005130) study, which essentially has been following 5115 patients, aged 18-30 years (initially) since 1986 to understand the effects of environmental, genetic, and personal factors on events later in life. To be included in this study (not in the larger CARDIA study itself), participants needed to have lived to year 15 of the study, met for examinations at least 3 times, and have a host of data collected on them throughout the study (see study link above for specifics).

At each of those 3+ visits during those 15 years, each participant was made to fill out a (fairly robust and in-depth) questionnaire2, which determined to what extent those people were meeting their 150min/week requirement for moderate intensity exercise over the preceding months/years. Data was only collected during those few visits, but a technique called Linear Interpolation was used to impute how active people were during the interim periods of time. The assumption was that overall physical activity changes between times when they were “directly” measured was linear. In my opinion, this is a pretty large assumption, but in the absence of ungodly amounts of money to constantly surveil patients or a time machine, this is as good as it gets.

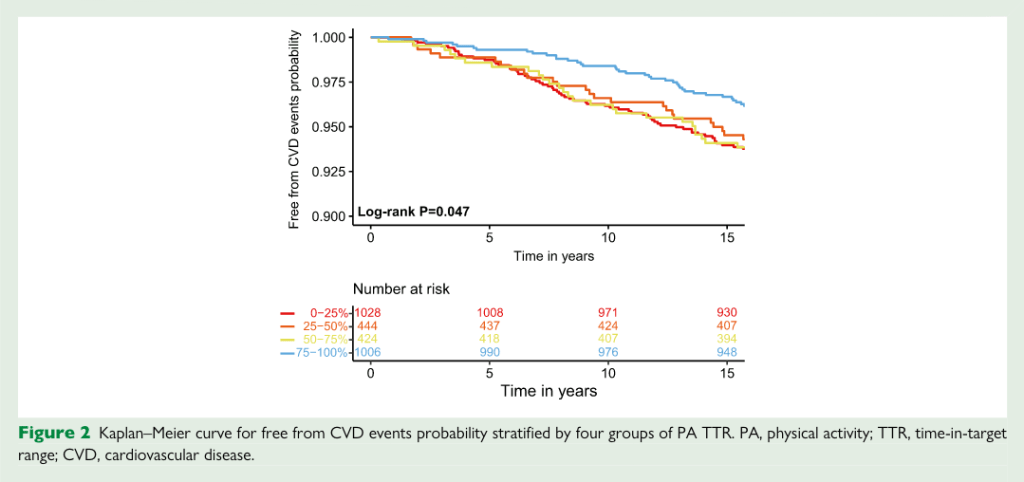

Lastly, Physical Activity Time in Target Range (PA TTR) was calculated by determining the amount of time during those 15+ years where the patients’ physical activity volume met the threshold for 150 mins/week of exercise (= 300 EUs). Patients were then categorized into four groups of 25% increments, and each of those groups were examined to assess how many cardiovascular events occurred. Secondarily, since all of the subjects who were analyzed for this study had coronary artery CT scans done, each of the four groups was examined to characterize how the level of coronary artery calcification progressed in relation to various levels of exercise output (but for the purposes of this discussion, we’ll leave this bit out).

What They Found:

Firstly, there was a statistically significant difference between those that achieved their target of 150 minutes/week of moderate intensity exercise (=300 exercise units) MOST OF THE TIME (=at least 75% of the time) and the number of cardiovascular events that happened after year 15. This is seen both in the Kaplan-Meier plot (used to show how patients remain disease-free over time) where the blue line breaks away from the rest of the pack pretty substantially and in Table 2 where the group of patients with PA TTR>74% had a statistically significant association with decreased cardiovascular events. In fact, the hazard ratio (a statistical metric used to describe the rate of occurrence of an event at a given point in time) for cardiovascular events in patients who achieved PA TTR>74% was 0.60, and this was persistent even after adjusting for covariates including: BMI, smoking, blood pressure, LDL-C, etc.

In other words, there was a 40% lower association with fatal and non-fatal heart attacks, heart failure hospitalizations, strokes, and procedures for peripheral artery disease in subjects who were closer to reaching their weekly requirements than those that were not. Furthermore, there was a statistically significant linear trend between the amount of exercise done and the number of cardiovascular events, which intuitively makes sense. When presented a different way, every 38.4% decrease in PA TTR was associated with a 21% reduction in cardiovascular events.

Why It Matters:

- Significant Long-term Benefits Observed Early in Life: What I found particularly notable was that the median length of follow up was 18.9 years and the average age of the participants (at onset, I believe) was 40.3 years, so roughly by age 60 there was 40% reduction in cardiovascular events. Since this isn’t a randomized controlled trial, and no “treatment” was prescribed to them, it is reasonable to assume that the extent to which the participants were exercising was established even prior to the study onset. If you assume that the people who were hitting 75%+ of their exercise output on a weekly basis have been doing so since they were in their 20s-30s, it only took until early middle age to see a marked difference in heart attacks, strokes, etc. In the grand scheme of things, 60 years of age is quite young! While you cannot strictly draw causality from the findings, an effect size of 40% in a relatively large study is hard to ignore — suggesting that if you exercise at least roughly 150 min/week at a moderate clip at least 75% of the weeks, you’re getting significant cardiac benefit. (Now imagine if you compared the subjects in the 75%-and-up group with sedentary individuals (the 0-25% group includes some of these but not all) — the discrepancy between the groups would be MASSIVE.)

- Exercise, the Great Integratory of Health: As the authors stated, the precise mechanisms that give exercise its ability to prevent cardiac events are likely multifactorial and not completely elucidated yet. And furthermore, given the observational quality of the study, you technically cannot infer causality. However, if you ask me, in this case it…really just doesn’t matter. Exercise, both cardiorespiratory fitness and strength, is the holy grail for disease prevention because it is the Great Integrator of Health (thank you, Peter Attia, for the analogy). Fine, this study isn’t a randomized control trial and we can really only say there is a STRONG association between exercising often and preventing cardiac events because we aren’t controlling for all the other stuff ahead of time, but in this case, that’s sort of the point.

Chances are that if you’re able to exercise 150 minutes a week at moderate intensity, week after week (at least 75% of weeks, to be exact) for decades, you’re probably taking care of a lot of the other stuff. In order to jog 30 minutes a day 5 days a week during your 20s, 30s, 40s, and beyond — when you’ve got a job and kids and hobbies (hopefully) — means that you’re probably not going to happy hour 3x/week. It means that you’re probably not staying up too late to binging that extra episode of Succession, because those morning workouts are just untenable when you haven’t slept. And if you’re more than just a weekend warrior, you’ve noticed that certain foods make it easier to spend that extra time in the gym while others just don’t. In other words, yes, regular exercise likely improves your lipid profile, reduces inflammation, and improves metabolic function, but BEING (see: Identity-Based Habits) someone who exercises regularly also likely means that you’re someone who does a host of other things that is associated with better outcomes.

- Maybe you can guess why that is (Hint: imagine how much money/effort it would cost to follow thousands of people for decades, split them into groups where they are forced to adhere to a certain amount/intensity of exercise — no more, no less — and then characterize how people die.)

- Now, as an aside, it must be stated that questionnaires are notoriously ineffective when it comes to encompassing what exactly people have done previously. If for no other reason, this is because humans have bad memories. Study after study has shown us that regardless of how good of a historian you think you are, when it comes to actually remembering what you ate last Tuesday or how far/vigorously you jogged over the weekend, when compared to objectively measured data, we are almost always off — way off. This is one of many reasons why observational studies are considered lower quality as compared to strictly experimental studies like randomized controlled trials. However, given the resource concerns mentioned above, questionnaires are all we got. Luckily, the questionnaire used for this study was quite robust. It was validated for accuracy in separate studies, and importantly, it asked an array of questions about involvement in various types of exercise and occupational activities. All types of activities were weighted based on their intensity, and ultimately, physical activity was volume summed in exercise units (EUs). Specifically: “Physical activity volume was the sum of scores of the intensity score times the number of infrequently performed months plus three times of intensity score times the number of frequently performed months of each PA.” (I wasn’t quite sure how this formula was decided upon, but it seemed reasonable enough)

Leave a comment