Source Research:

“2-Fold More Cardiovascular Disease Events Decades Before Type 2 Diabetes Diagnosis”

Authors:

Christine Gyldenkerne, Johnny Kahlert, Pernille G. Thrane, Kevin K.W. Olesen, Martin B. Mortensen, Henrik T. Sørensen, Reimar W. Thomsen, Michael Maeng

What We Already Know:

Type 2 diabetes (T2DM) is one of the most common, rapidly growing, and significant diseases associated with cardiovascular conditions like heart attacks and strokes. In fact, the current 537 million adults with T2DM are projected to skyrocket to almost 800 million by 2045. However, it’s unclear whether having T2DM itself—or the myriad conditions tightly linked to it—is the main driver behind the development of heart disease. These associated conditions include poor lifestyle habits, genetic predisposition, metabolic syndrome, obesity, and environmental factors.

What we do know is that many of these syndromes cluster together. In diabetics, aggressively managing this cluster with diet (if it leads to weight loss), physical activity, and medications (especially some newer ones) decreases mortality rates. Interestingly, simply lowering average glucose levels into the normal range through medication—without addressing weight, blood pressure, or cholesterol—does nothing to prevent premature death. While treating diabetes itself can improve or prevent microvascular complications like neuropathy, nephropathy, and retinopathy, the real issue lies in the metabolic dysfunction closely tied to diabetes.

But what if this metabolic dysfunction exists long before a patient is diagnosed with T2DM?

What Was Done:

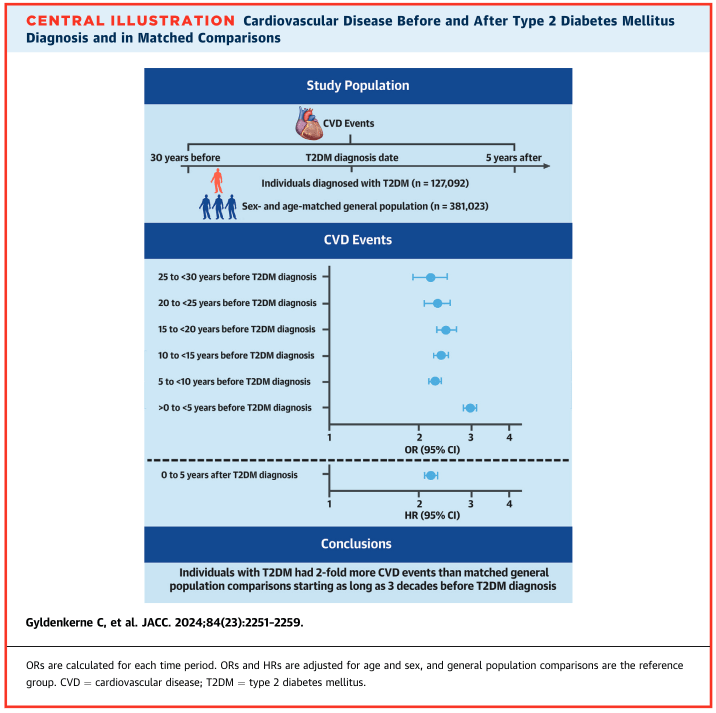

Researchers identified all patients in Denmark diagnosed with T2DM between 2010 and 2015 using their centralized healthcare registry (yay, universal healthcare—yes, we know it’s not perfect, so no need for pitchforks).

Controls without diabetes were selected from the same population for comparison. Medical records for both groups were examined for the first evidence of cardiovascular disease (CVD, including heart attacks and strokes) occurring anytime between 30 years before and 5 years after the diagnosis of T2DM.

What They Found:

Among the 127,092 patients diagnosed with T2DM and their 381,023 control patients, there was a 2- to 3-fold increase in the occurrence of CVD events up to 30 years prior to a diabetes diagnosis:

- 25 to <30 years prior: Odds Ratio = 2.18

- 5 years after diagnosis: Hazard Ratio = 2.20

When the analysis was adjusted for cardiovascular risk factors (e.g., age, sex, hypertension, dyslipidemia, hospital-diagnosed obesity, and smoking), the results remained largely unchanged.

Why it Matters:

Patients with Type 2 Diabetes are…late to the party.

If you’re diagnosed with T2DM, chances are you’re already at a significantly elevated risk for cardiovascular events, such as strokes or heart attacks. The same metabolic dysfunction driving this risk doesn’t just manifest when your Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) percentage surpasses 6.5%. This study demonstrates emphatically that patients who go on to develop T2DM already face double the odds of CVD decades before anyone even mentions the word Ozempic. That something is the metabolic syndrome of which diabetes is simply a facet — and often a lagging one.

If you wait until you’re labeled diabetic to make lifestyle or pharmacological changes…you’re asking for a bad time.

Let’s say you went for a work physical at age 45 and were told that your Hgb A1c% was 7.1. Some might say, “Well, that’s not too bad. Start some metformin and be done with it.” It pains me to know that some of those people are probably physicians themselves. Sure, after three months, your Hgb A1c% very well could be 5.5%, but if taking that medicaiton is the only thing you’ve done, you haven’t done anything to address your CVD risk, and the again, the damage has been going on for years…

The more pressing issue is metabolic syndrome.

While diabetes itself gets much of the attention, the more fundamental issue is insulin resistance — and taken a step further, metabolic syndrome. I’ll save the history lesson for another day, but briefly, it was noted in the 1920s-1930s that patients with some combination of diabetes and obesity were at higher risk of cardiovascular disease. In 1988, Dr. Gerald Reaven formally presented a constellation of risk factors—insulin resistance, hyperglycemia, hypertension, and dyslipidemia—as “Syndrome X,” later renamed Metabolic Syndrome (MetS). Moreover, several large studies have repeatedly born out the link between MetS and CVD.1

As it stands today, the diagnostic criteria for Metabolic Syndrome is as follows (with 3 of the 5 necessary to clinch the diagnosis):

- elevated waist circumference: ≥40 inches in men, ≥35 inches in women

- insulin resistance: fasting glucose ≥100 mg/dL

- elevated triglycerides: fasting triglycerides ≥150 mg/dL

- low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C): fasting HDL <40mg/dL

- high blood pressure: systolic blood pressure ≥130mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥85mmHg

As seen above, an elevated fasting glucose level, which is essentially the continuum upon which prediabetes and T2DM sit, is but one of the 5 criteria for MetS. Firstly, notice how the criteria specify a cutoff of 100 mg/dL, which actually corresponds to the clinical cutoff for prediabetes (also equivalent to a Hemoglobin A1C% of 5.7-6.4). In other words, even before someone formally meets the cutoff for T2DM, he/she is showing evidence of insulin resistance and metabolic disease.

Metabolic disease is on a spectrum, and we ought to be treating it much sooner.

Studies have shown that even when patients are under the clinical diagnostic threshold of MetS, they suffer from high rates of cardiovascular disease. Similarly, even with insulin resistance, patients who are prediabetic have higher rates of CVD. Today’s study fleshes this out further. Up to 30 years before diagnosis of T2DM, these patients had over double the rates of CVD. While the specific metrics of their various metabolic diseases were not parsed out in the study (e.g. Hgb A1c% at time of cardiac event, body mass index, blood pressure, cholesterol levels), I suspect that the patients who had CVD and eventually went on to be diagnosed with T2DM probably already had these other signs of MetS years before.

While this study was conducted in Denmark, given the worse rates of metabolic disease in the United States, I’m sure similar findings would be born out if a similar study could be done here (if not much, much worse). Yes, healthcare policy and public health resource allocation is difficult, at best, but the fact anyone is being diagnosed with T2DM after they’ve already sustained a heart attack or stroke is…a travesty. It is simply emblematic of misplaced incentives: we don’t place nearly enough emphasis on prevention and screening.

Why wait until someone’s Hgb A1c% is 5.7 or their waist circumference is 40 inches to do something about it. Let me pose the question another way: taking the criteria for MetS above, if a gentleman, let’s call him Mr. P, walks into a primary care clinic with the following metrics, are you sending them on their merry way?:

- a waist circumference of 38 inches

- fasting glucose of 95 mg/dL

- fasting triglycerides of 145 mg/dL

- fasting HDL-C of 42 mg/dL

- blood pressure of 128/83 mmHg

I sure hope not…Just because they don’t meet the strict cutoffs for T2DM or MetS is not to say they don’t have significant metabolic disease. And who knows, perhaps all 5 criteria being just below the cutoff translates to worse outcomes than having 3 criteria clearly beyond the cutoffs. We haven’t accounted for ethnicity (what if Mr. P is actually Mr. Prasad?) since some ethnic groups like South Asians have more strict cutoffs because of their higher baseline risk for CVD (more on this another time). We’re also not looking at his other cholesterol markers, his family history (a good marker for overall genetics), his physical strength, etc. Unfortunately, plenty of providers wouldn’t be bothered by the above risk profile.

Others have likened prediabetes/metabolic syndrome to a ticking clock. I say it’s more of a ticking time bomb. Instead of waiting until the damage is done and patients have already lived with decades of metabolic dysfunction, patients and doctors should be on the lookout for signs of metabolic disease as early as possible.

Practical Considerations — pay attention to the following/things to ask your doctor:

- Body mass index (BMI)/waist circumference

- Visceral fat (fat in/around your organs) is bad, but it’s difficult to quantify.

- Patients who carry extra subcutaneous fat tend to also have visceral fat, so we measure BMI and waist circumference.

- BMI isn’t perfect, and it tends to be quite inaccurate at the extremes of height and muscle mass, but if it’s reaching 25 kg/m², you need to start making some changes to your diet and cardiorespiratory training. (BMI Calculator)

- Normal cutoffs for waist circumference are ≤40 inches in men and ≤35 inches in women. If you’re nearing those, again, changes are needed.

- These are cost-free and easy to measure, so check them frequently.

- Insulin sensitivity

- There are several ways to impute this, including Hgb A1c%, oral glucose tolerance testing, fasting glucose measurements, etc.

- Checking Hemoglobin A1c% is the easiest and what 99% of patients get tested for because it simply requires a blood test and integrates one’s average blood glucose levels over the past three months. However, it’s not perfect. By itself, A1c only diagnoses about a third of the patients with T2DM who would be identified if Hgb A1c%, fasting blood glucose, and oral glucose tolerance tests were combined (more on this another time).

- Most guidelines recommend starting to measure at age 35 or sooner if BMI >25 or there are other risk factors (family history, presence of CVD, etc.). Measurements should be repeated every 1-3 years in patients without T2DM, depending on whether they have prediabetes.

- Blood pressure

- Oh boy, we’re not going into the weeds on this today, but suffice it to say your blood pressure should be less than 120/80 (though <130/80 is probably more appropriate for some patients).

- Everyone should have an upper-arm blood pressure cuff at home, and if you’re at risk of hypertension (high blood pressure) by way of family history or personal history, it should be checked at least daily. Preferably, it would be tested in the morning before breakfast and medications and in the evening prior to dinner.

- Cholesterol and triglycerides (much more on these in the coming weeks/months)

- Patients aged 20 and above should have a lipid panel checked at least every 4-6 years.

- Based on the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, children should be tested once between ages 9-11 to screen for obscure genetic diseases (like familial hypercholesterolemia).

- If there is a family history of early heart disease or severe cholesterol issues, children should be tested as early as 2 years of age.

- Everyone should be tested once in their lifetime for a type of cholesterol, Lipoprotein (a). Be sure to have your doctor check this, as it is highly under-checked and a significant driver of cardiovascular disease.

- MetS and CVD risk:

- Mottillo et al. (2010): Meta-analysis of 87 studies with 951,083 patients found that metabolic syndrome (MetS) is associated with a significant increase in the risk of CVD (RR: 2.35), CVD mortality (RR: 2.40), myocardial infarction (RR: 1.99), and stroke (RR: 2.27).

- Alshammary et al. (2021): Meta-analysis of 10 observational studies involving 9,327 participants reported that MetS is significantly associated with a higher risk of coronary artery disease (CAD) (OR: 4.03).

- Liu et al. (2021): Meta-analysis of eight studies with 36,614 hypertensive patients found that MetS is associated with an increased risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (RR: 1.55), cardiovascular mortality (RR: 1.44), and stroke (RR: 1.46).

- Su and Zhang (2023): Meta-analysis of 32,736 patients with stable CAD showed that MetS is associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality (RR: 1.22), cardiovascular mortality (RR: 1.49), and major adverse cardiovascular events (RR: 1.47).

Leave a comment